A Sermon preached at St Martin-in-the-Fields on July 14, 2024 by Revd Richard Carter

Reading for address: Mark 6: 14-29

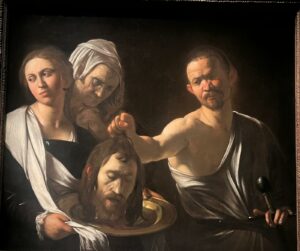

Next door at the National Gallery in the exhibition The Last Caravaggio, alongside The Martyrdom of Saint Ursula is another painting by Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio, Salome receiving the Head of John the Baptist, believed to have been painted in 1609-1610, the last year of Caravaggio’s own life. Like much of his life, Caravaggio’s final months were underscored by violence. This painting was painted in Naples where it is related that he was attacked leaving a tavern and his face so viciously slashed that he was almost unrecognisable. Despite the fiercest pain, Caravaggio boarded a boat and headed for Rome hoping to be granted a Papal pardon for a murder he had committed in 1606, but he succumbed to fever and died. In these final paintings we see the stark contrast of light and darkness and the enduring power of Caravaggio’s storytelling as he tells the story in his painting of the horror of violence and perhaps his own soul’s longing for redemption. Look at the picture, go and see it. It shows Caravaggio’s ability to render real people and to create timeless compositions which confront his audiences with dramatic moments that change everything. Here we see the executioner holding the hair of the severed head of John the Baptist carried on a platter by Salome.

Salome receives the head of John the Baptist Michelangelo Merisi Caravaggio, National Gallery

Look at Caravaggio’s painting for a moment. The executioner with the sword on the right. Is his face full of brutality? Or, as he holds the head away from himself, do we detect in his expression the realisation of the horror or shock at what he has done. Is it a face of callousness, or remorse, or neither? It is a face which seems to say, ‘Look, I have done what you wanted and now will forever live with the consequences of this act.’ How often do we look at people under judgement for their actions and wonder what is going on in their heads behind their eyes and how, or if, they can ever face up to what they have done. Now look at Salome on the right holding the plate and yet looking away. She has done her mother Herodias’ bidding – she has asked for the head of John the Baptist. Who is she looking towards now? Is she looking towards her mother who made her do this? Or is she looking towards her stepfather Herod, the one for whom she has danced, and as she has done so, entered into a manipulative flirtation – the result of which she now holds out on the platter. Now she looks away as though in revulsion or repelled by the consequences – or is that look denying responsibility – as though saying look what you made me do. Now look at the third figure looking down on the head as if in sorrow, the silent witness seeing all, is she grieving? Why does she stand so close to this horror? Who is she? Does she represent us, the onlookers, who see the horror but cannot distance ourselves. And finally look down at the head of John the Baptist. The head from which the lifeblood has drained, a head with eyes downcast, which seems to contain all the sorrows of the world and yet is strangely peaceful; this lifeless head with its expression frozen in an eternal prayer. The moment you kill your supposed enemy, they escape you. They are no longer your prisoner. You have become the prisoner of the action you have carried out. All that led to that action of evil – the jealousy, the desire, the power, the lust, the excitement of the dance, the manipulation – all this is now frozen here in the realisation that John the Baptist, victim of this power game, is in fact the only one at peace. John the Baptist, the one who comes before Christ to prepare his way, has once more gone before Christ to prepare his way to the kingdom. In John’s face we see the light of Christ – John, the one sent by God who came as a witness to the light – the light which shines in the darkness and which the darkness can never put out.

There is horror for us all in the image of decapitation. The head is all that gives expression and dignity, sight, sense, voice and personhood to the body, now severed. The execution is meant to mock human life, taunting us with our own mortality. Throughout history beheading has been used as a method of instilling fear and humiliating one’s enemy and gaining power. The traitor’s head spiked on the gate, severed from authority, a warning. Kings and queens and traitors or martyrs executed on the block. In the French revolution – the guillotine. Still today we think of terrorists, like the crimes of ISIS, cutting off the heads of their victims as if not only to kill but also to desecrate the body of the victim, like the last act of sacrilege. Rendering the body of your enemy profane, dismembered and cursed. Yet in Caravaggio’s painting the violence of the action has failed to defeat their victim. Instead, his head seems sacred, bathed in a light that lights the actions of the perpetrators. This is the one who has called us all to behold the Lamb of God who will take way the sins of the world.

I have been reading the powerful story of Diane Foley in a book entitled American Mother. It tells the true story of how Diane seeks to meet Alexander Kotey, now in prison for life in USA, one of the members of the infamous so called Beatles in ISIS who had been involved in the torture and public beheading of her journalist son James Foley. Diane is a Christian seeking to understand her son’s death and in so doing she sheds light. She humanises rather than simply demonises the one who has caused her son, and all who loved him, such terrible suffering and pain. This is how their meeting is described:

‘Give me mercy, give me strength,’ she prays as she meets him. She is overwhelmed by sadness – sadness that her son Jim is dead, sadness that Alexander Kotey, accused of his torture and murder, will spend the rest of his life in prison in isolation and never know his three daughters, sadness that nobody knows what innocence means any more, and sadness that we still go on taking and wasting the lives of one another. The sadness that comes down to either justice or revenge, as if that is the only choice, the sadness that very sadness itself is not an answer.’ Diane knows in her soul that hatred is not the answer. ‘She knows that she will be called naïve, she knows that the media will say that she has been duped by a terrorist, that she has fallen for his act, allowed herself to be open to his deception, but to her that does not matter, not a bit. She allows herself for the first time since her son’s murder to cry, cry. Not words of condemnation but simply tears in the presence of Kotey. Tears not just for her son who is at peace but tears also for the one involved in his death who must live all his life with the memory of what he has done.’

‘I hope one day we can forgive one another,’ she says to Kotey.

Kotey is taken aback. ‘There is no reason for you to offer forgiveness,’ he says. At their last meeting, though she knows it is contrary to his Islamic practice to touch a woman she offers Kotey her hand and he takes her hand and she says to her son’s torturer, ‘Peace be with you.’ Later he is asked why he accepted to take her hand and Kotey replies, ‘She’s a mother, a mother to us all.’

Our Gospel leads us on that same journey and it is as though this act of evil is pointing beyond itself to Jesus. It is sandwiched between Jesus sending out his disciples and their return. The whole gruesome story of the death of John the Baptist is the first part of Mark’s Gospel that does not have Jesus at its centre. This is because Mark is using this story of John to show us something essential about discipleship, that following Jesus will cost not less than everything. Time and time again the love of Christ will come into confrontation with the full horror of all that opposes. Jesus too will be condemned to death before Herod in a tragic power game. John’s story is the prelude to the passion of Christ. Our Gospel story is not just the story of a gruesome piece of history during the time of Jesus. It is the story of all of us who get involved in the betrayal of goodness, who manipulate power and then find ourselves the victim of the tragedies we have perpetrated. You may say this has nothing to do with us today, while the world watches the pictures of Israel and Gaza where they say in the last nine moths 38,000 people – woman, children, the innocent, the hostages – have lost their lives.

In this story there is no mistaking the horrifying power of human complicity in evil. The story of John’s death is extreme but recognisable. Herodias’ jealousy infecting her daughter with malignity. Herod’s pride and reputation and sexual gratification more important than the loss of an innocent life. Such squalid betrayal is recognisable – the fear of losing face, the fear of standing up for the falsely accused, the fear of speaking out for the victim when faced by the majority, the fear for our own reputation, that we too will be tarred with the same brush as the scapegoat. It is the fear of living the Gospel and of actually trying to love one’s enemy; the fear of having compassion for one’s enemy; the fear of releasing prisoners. The fear of forgiveness or redemption without which there is NO future.

John the Baptist is the forerunner. We have been given an insight into the struggle to come which will take Jesus Christ to the cross and his disciples will scatter in confusion fearing to be tainted by or accused of the sins of their former master and friend the one now stripped naked, seemingly humiliated and defeated and nailed to a criminal’s cross.

In our lives we often see death as the end of the story. By beheading their enemy they think they have defeated their enemy, far from it. It is John the Baptist who will live on just like the Lamb of God to whom his life testifies. The light can never be put out. It is Herod and Herodias and Salome – who must face the evil they have committed – their death in life. It is as though his light is shining on them just as it does in Caravaggio’s painting.

Is not the Christian story about the life of the crucified one – we forever carrying in the body the death of Jesus, so that the life of Jesus may also be revealed in our mortal bodies.

Jamie, who died 10 days ago in St Mary’s Paddington Hospital, wrote these words:

In the depths of depression we die

Our ego dies, our hope dies

And in this death we are reborn

Emptying ourselves of our ego can let God into the depths of our soul

This Easter story of resurrection begins many times over

Where breakdown becomes breakthrough and we are born again and again from above. I believe, wrote Jamie, there is a little piece of God in each one of us, in all of God’s creation. It’s called the soul. It’s like the candle at the core of our being. Although it sometimes feels like God cannot go out. [1]

Yes we often see death as the end of life not the beginning. But if it is the beginning, as Christ has promised, how then must we live?

[1] Gemma Poncia: Reflections of a Voice Hearer 3rd Edition